A short but information-rich itinerary: visit one of the best outcrops of the K/Pg (Cretaceous-Paleogene) boundary in Cuba, marking the moment of the dinosaur extinction due to the impact of a large meteorite, and explore the Great Cavern of Santo Tomás, an extended adventure into a natural, unlit cave.

El itinerario se inicia en la carretera de Viñales a Pons, pocos metros después del en tronque con la localidad El Moncada. La primera parada es en la carretera para ver el límite K/ Pg, momento de la extinción de los dinosaurios, la segunda es una observación de rocas calizas y la tercera la visita de la Gran Caverna de Santo Tomás, más que una visita es una aventura espeleológica en una cueva en su estado natural.

GEOSITIOS

1. The Extinction of the Dinosaurs

Layers of limestones and sandstones

Cretaceous-Paleogene Boundary

The Stratigraphic Column

2. Siliceous Breccia

Limestones with dark angular fragments

Breccia of limestones with fragments

The Stratigraphic Column

3. Great Cave of Santo Tomás

Descent of the water table level

Descent of the water table level

Karst

CURIOSITIES

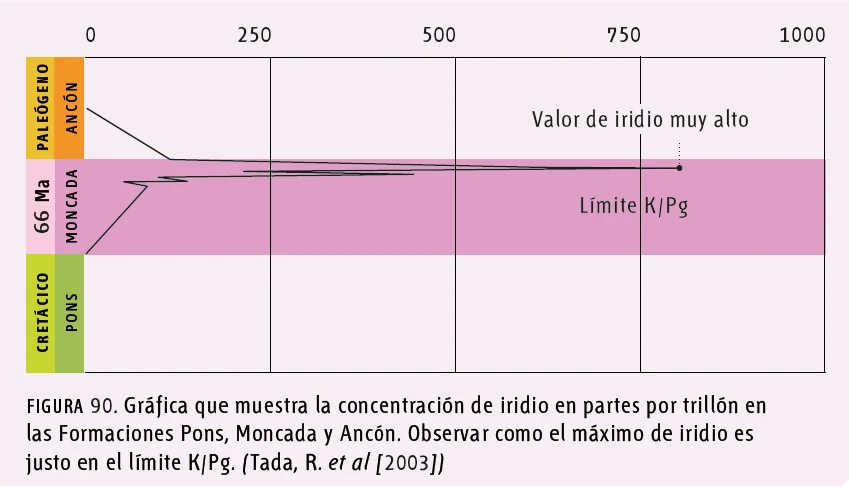

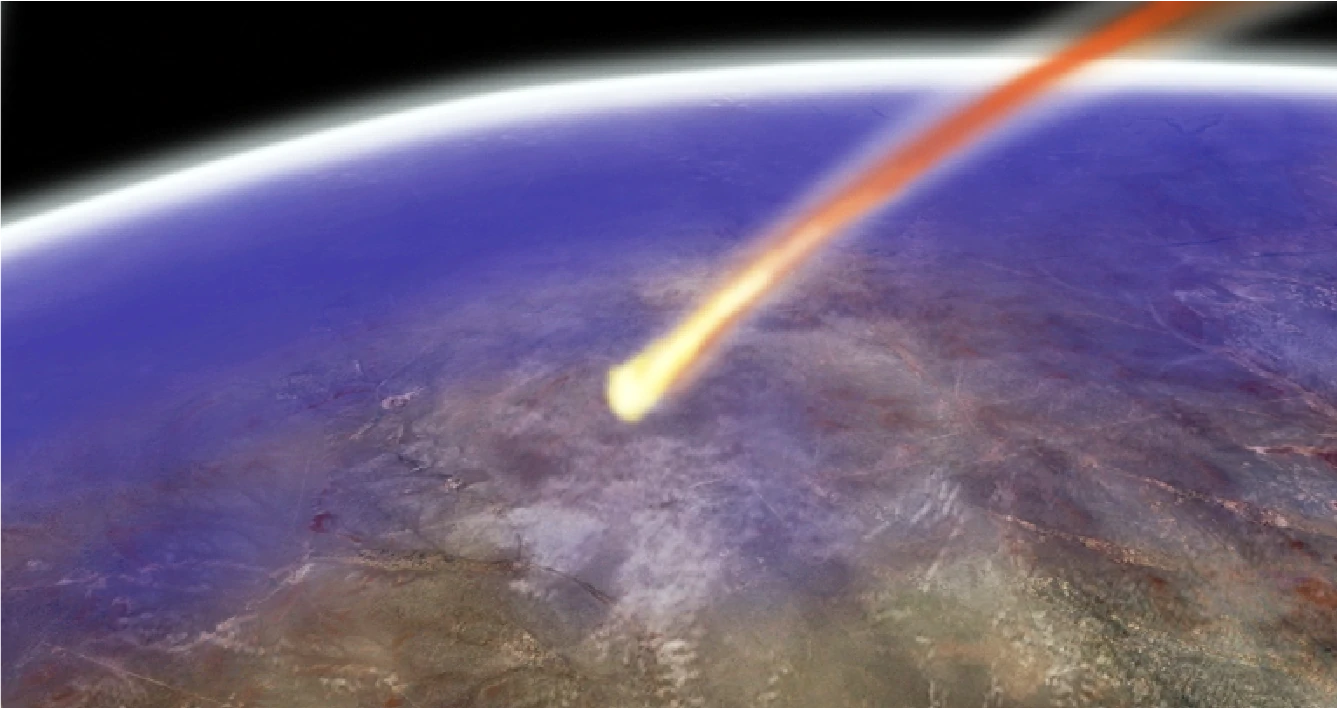

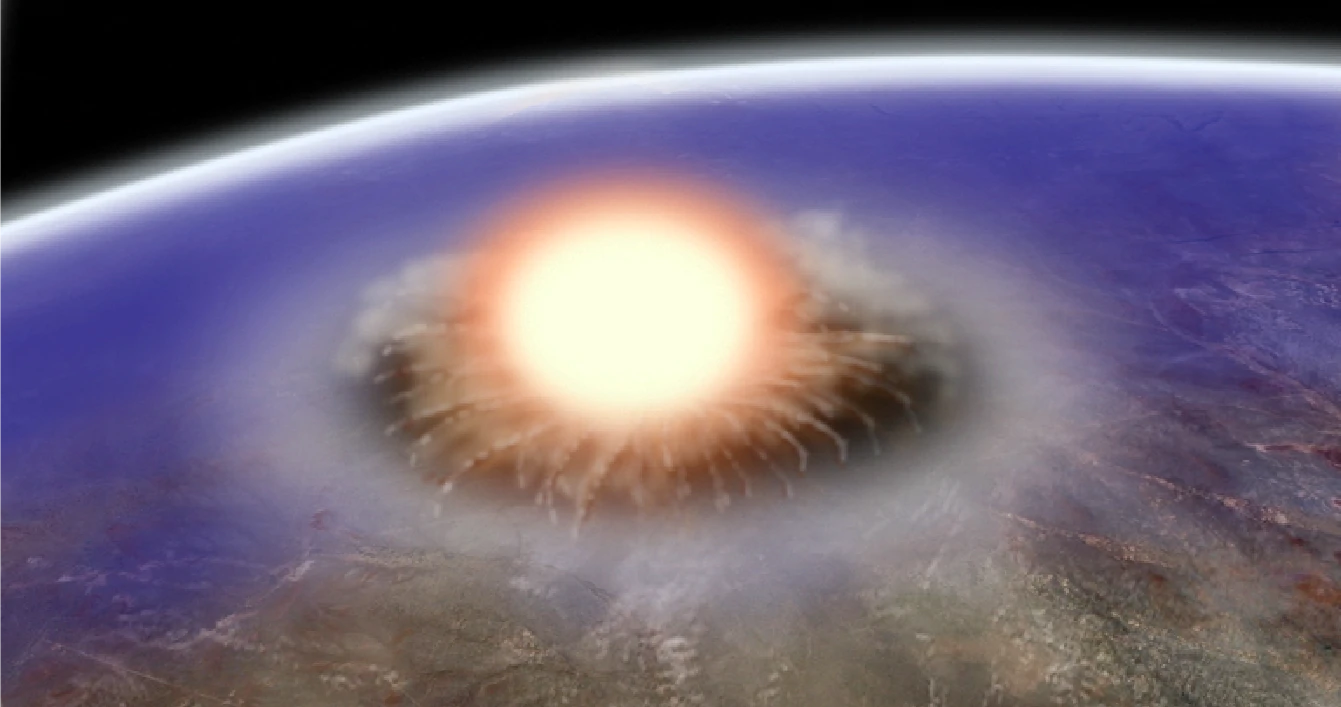

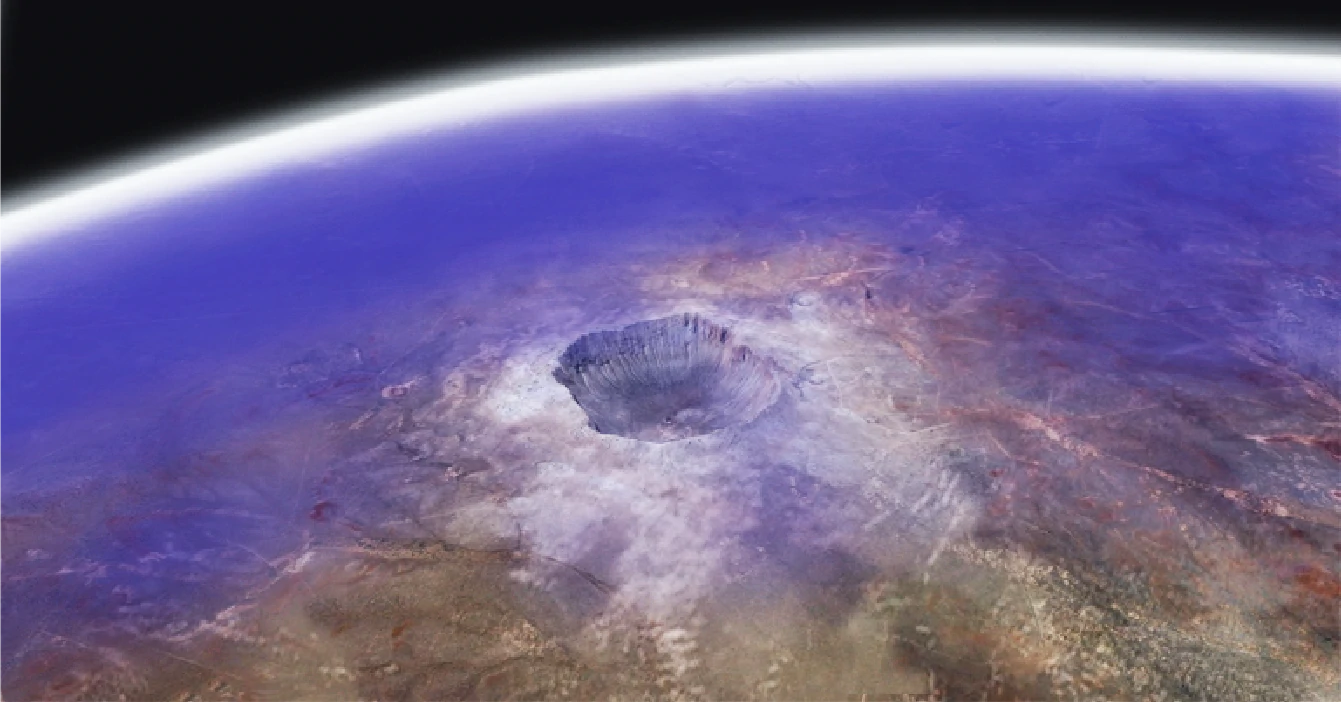

We know that at the boundary between the Cretaceous and Paleocene, 66 million years ago, a mass extinction of organisms occurred. Among the most affected were the dinosaurs, gigantic animals that ruled the planet for over 180 million years, from the Triassic to the Late Cretaceous. After this event, the ecological void left by the dinosaurs was filled by a proliferation of mammals.For many years, the reason for the dinosaurs’ extinction remained a mystery. Scientists debated various hypotheses until they discovered, in several locations worldwide, that sediments at the Cretaceous-Paleocene boundary contained high concentrations of iridium. This level is called the K/Pg boundary (between the Late Cretaceous (K) and Paleogene (Pg), 66 million years ago. Iridium is rare on Earth but abundant in meteorites, suggesting that a large meteorite impact might have caused the extinction. The missing piece was finding the enormous crater created by such an impact. This was discovered in the northwest of the Yucatán Peninsula (Mexico)—the Chicxulub crater, over 180 km in diameter, not far from ancient Cuba. Evidence found there confirmed the meteorite impact: anomalous iridium, tektites (natural glass formed by meteorite impacts), gravitational anomalies, and shocked quartz.

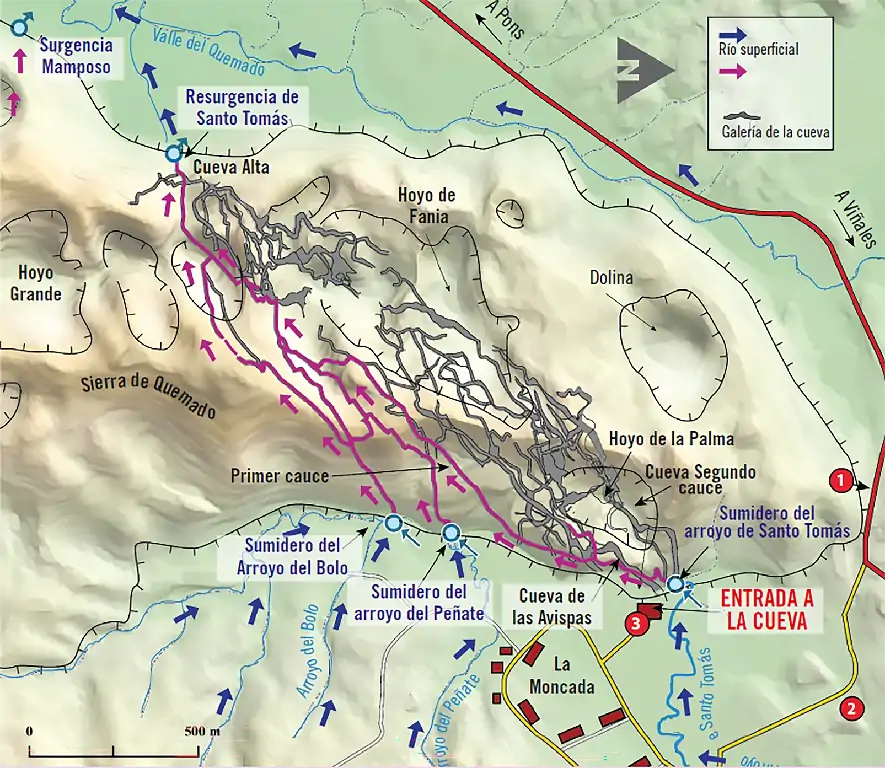

In the Quemado Mountains, there’s a network of underground galleries spanning about 46 km. The Santo Tomás River and other streams, like Bolo and Peñate, flow over impermeable rocks (Manacas Formation) on the surface. When they reach the massive limestones of the Guasasa Formation, they go underground through various sinkholes. These underground rivers re-emerge in the Valle del Quemado on the western side of the mountains. Thousands of years ago, the first underground rivers formed but were abandoned as the water table dropped. Over time, the water table continued to descend, leaving upper galleries dry. Today, seven levels have been mapped. The most recent is the active underground river, called the "First Level." Above it is the "Second Level," which often has water in certain sections and floods during high water. The five upper levels, increasingly older, are named: Level 3 (Mesa Cave), Level 4 (Antorchas Cave), Level 5 (Incógnita Cave), Level 6 (Avispas Cave, the one visited), and the oldest, Level 7 (Alta Cave).A simplified map of the Great Cave of Santo Tomás shows its 46 km of galleries across seven levels. Streams from the eastern sector enter through sinkholes and re-emerge in the Valle del Quemado. Cross-sections illustrate the evolution of the Santo Tomás system, with the oldest levels at the top and the most recent at the bottom, marked by the underground river’s path (vertical scale exaggerated).