View of the isolated mogote of Zacarías, the incredible discovery of a closed valley (Hoyo de Jaruco), caves with fossils and cave paintings.

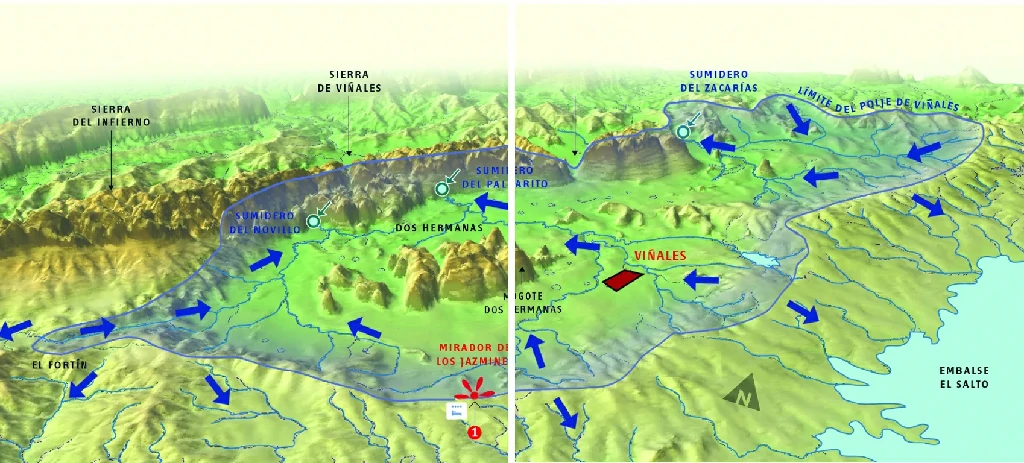

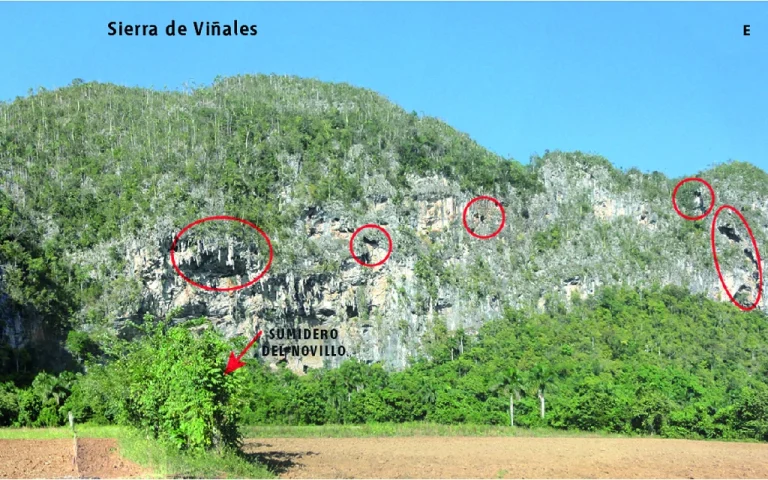

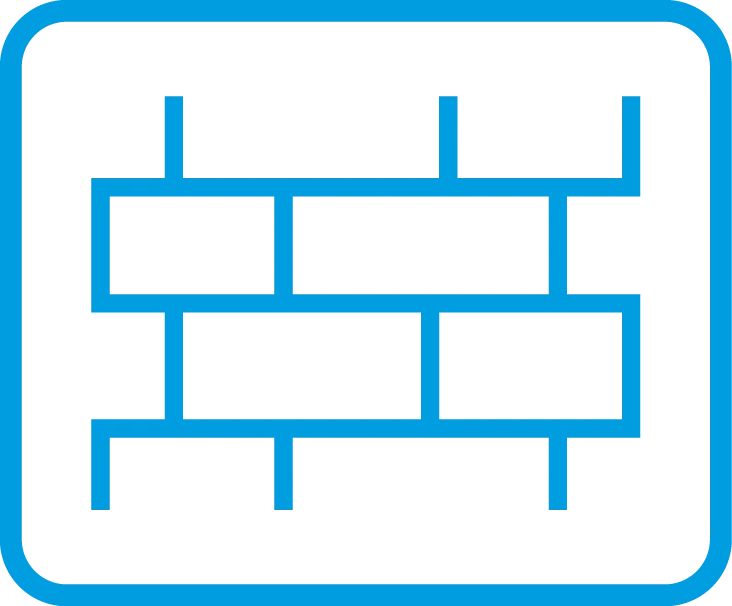

The itinerary begins at Los Jazmines, an exceptional viewpoint of the Viñales Valley, and visits the Viñales National Park Visitor Center with information and a model of the area. The next stop is at the entrance to Dos Hermanas, an example of rocks isolated by erosion that resemble a small "Stonehenge" Mural of Prehistory, allegorical paintings of the geological evolution of Cuba on the rocky wall of a mogote. Visit to the Dos Hermanas paleontological museum. Panoramic view to the south of the mogotes and Novillo sinkhole, a river that crosses the Viñales Mountains to resurface in the Ancón area (Itinerary 5).

GEOSITES

1. Los Jazmines

Unique panorama

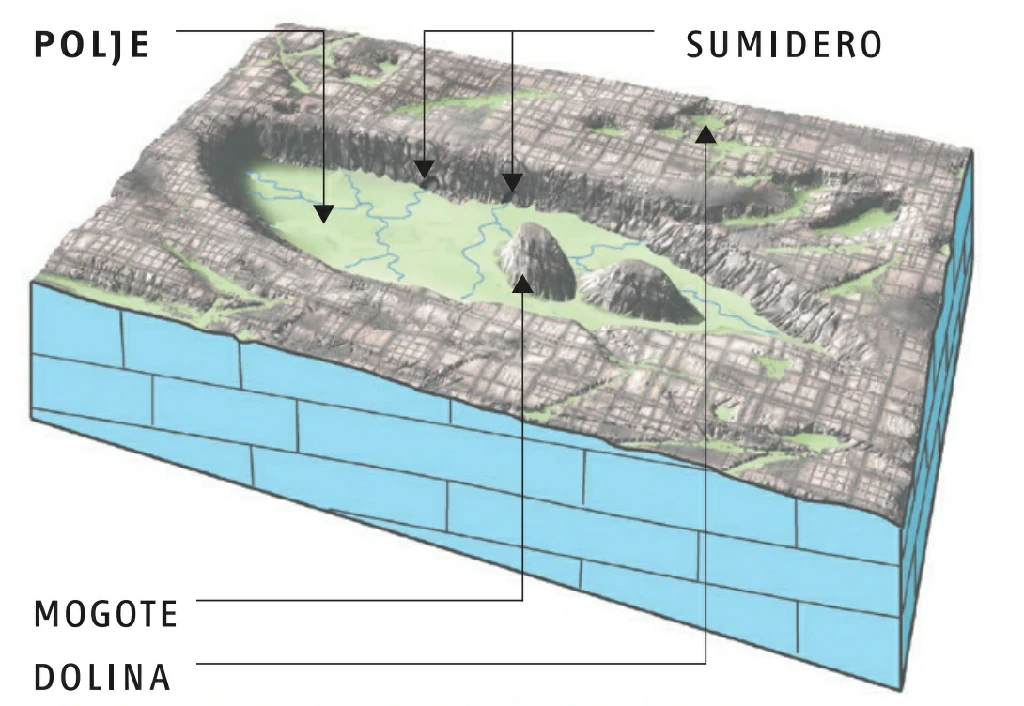

Mogotes of karst origin

Karst evolution of Viñales Valley - Why are there mogotes?

2. Visitor Center

Geology

Natural sciences

The geological setting of Viñales

3. The small "Stonehenge"

Isolated vertical rocks

Remains of superficial karst forms

Karst evolution of Viñales Valley

4. Mural of Prehistory

Mural on a rocky wall

Representation of Cuba's history

5. Dos Hermanas Paleontology Museum

Fossils

Fossil examples and information

The fossils of Viñales

6. 360° Panorama

Area surrounded by mogotes

Action of karst erosion

Karst evolution of Viñales Valley

7. Novillo Sinkhole

Stream entering a cave

Karst sinkhole

Karst evolution of Viñales Valley

CURIOSITIES

At the Los Jazmines viewpoint, there is a monument with a bust of the painter Domingo Ramos, considered the painter of the valley, as his landscape works made known to the entire world the beauty of the mogotes. He was born on November 6, 1894, in Güines, and died on December 23, 1956, at the age of 62. From an early age, he showed his vocation for painting and had the opportunity to study in Havana, at the San Alejandro Academy. He gained popularity from a contest organized by the magazine Bohemia in 1912; later, he received a pension from the Cuban government to continue his studies in Madrid, at the San Fernando Academy. In the early 1920s, he decided to settle in the Viñales area to dedicate most of his time to painting landscapes of the valley.

His international fame began in 1923, with a show of thirty-eight works exhibited in a venue of the Diario de la Marina in New York. This exhibition contributed to consolidating his prestige as a creator and making Viñales known. On that occasion, he won the bronze medal and provoked the astonishment of specialized critics who did not accept the idea that what was exhibited in Ramos's work was a real landscape. The viewpoint where we are is thanks to the efforts of the Lions Club, which in 1939 proposed building a viewpoint on the Loma de los Jazmines to facilitate the observation of the landscape, right in the place from where Domingo painted.

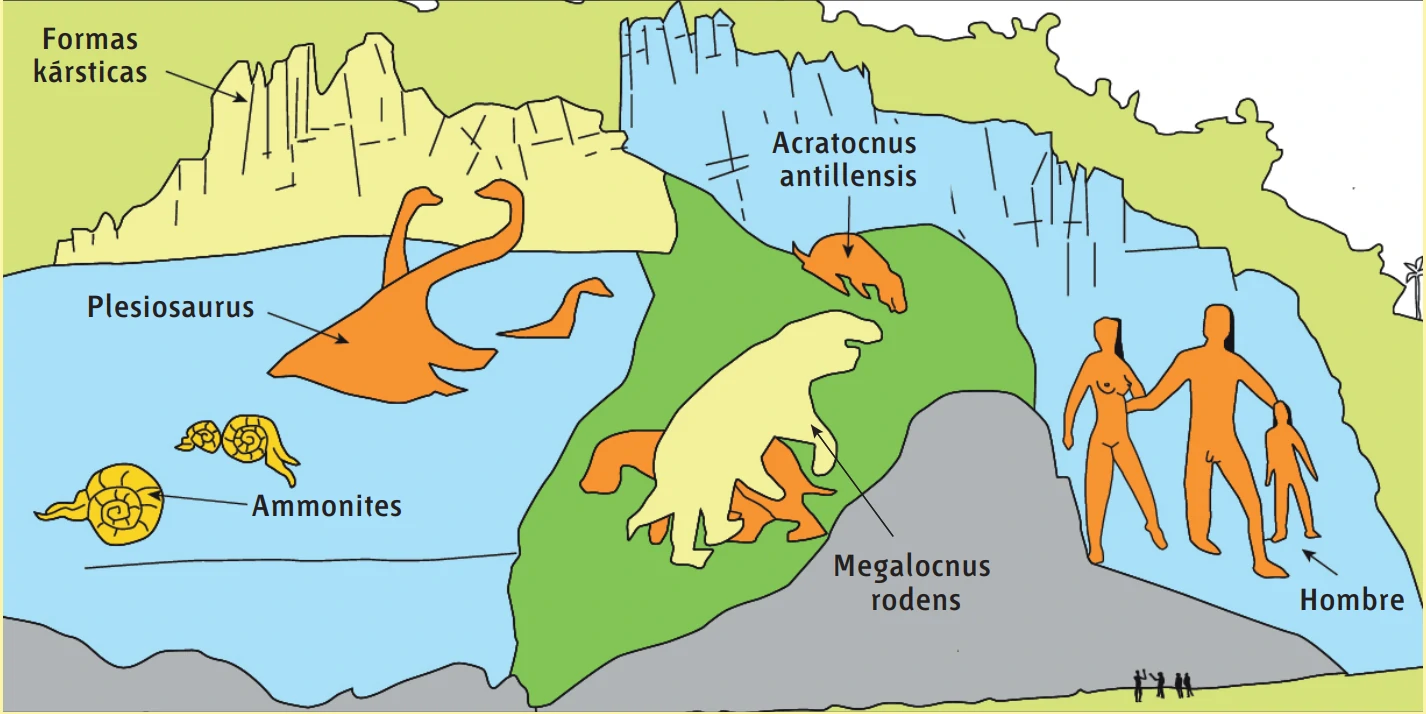

The Mural of Prehistory, one of the largest open-air frescoes on the planet, represents the biogeological past of the region, with human and animal figures, now fossils, that inhabited this area.

The majestic work, 120 meters high, is painted on Jurassic-period rocks with evident signs of karstification, especially in the upper part. It was created in 1959 by the painter and scientist Leovigildo González Morillo (a disciple of the Mexican muralist Diego Rivera).

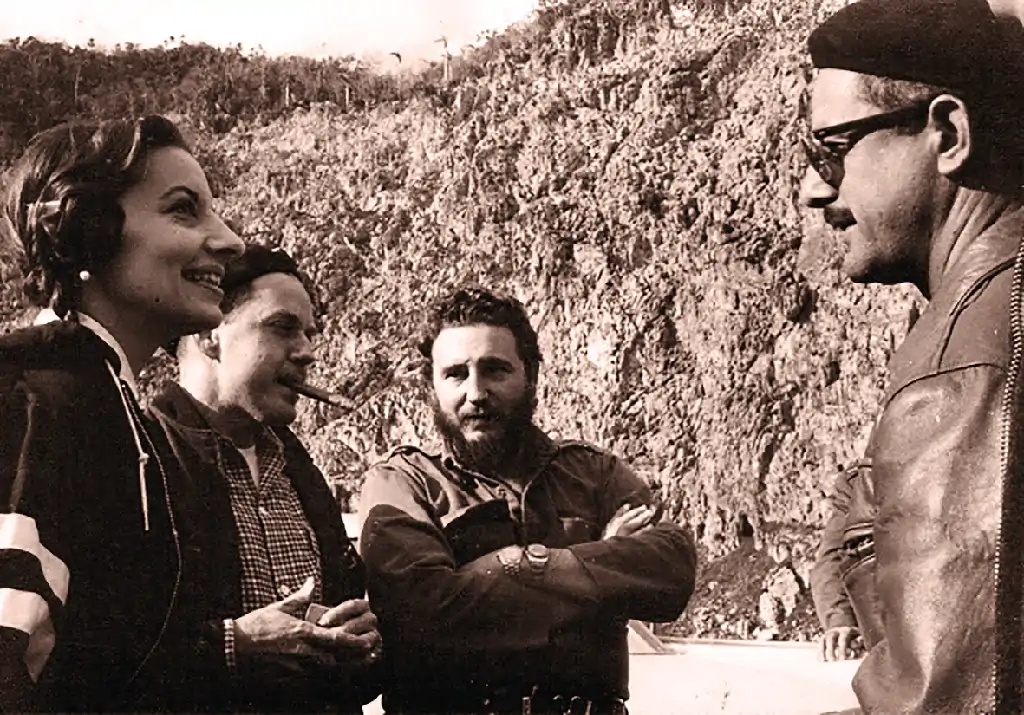

The painter Leovigildo González together with Commander in Chief Fidel Castro Ruz and the dancer Alicia Alonso exchange about the work.

El pintor Leovigildo González junto al Comandante en Jefe Fidel Castro Ruz y la bailarina Alicia Alonso intercambian sobre la obra.

Lower Jurassic ammonites

The lower left part represents the oldest epoch of Cuba, the Jurassic, with an age of about 203 Ma. On a blue background representing the sea, three specimens of yellow ammonites have been represented, cephalopod mollusks with a spiral shell that lived at that time.

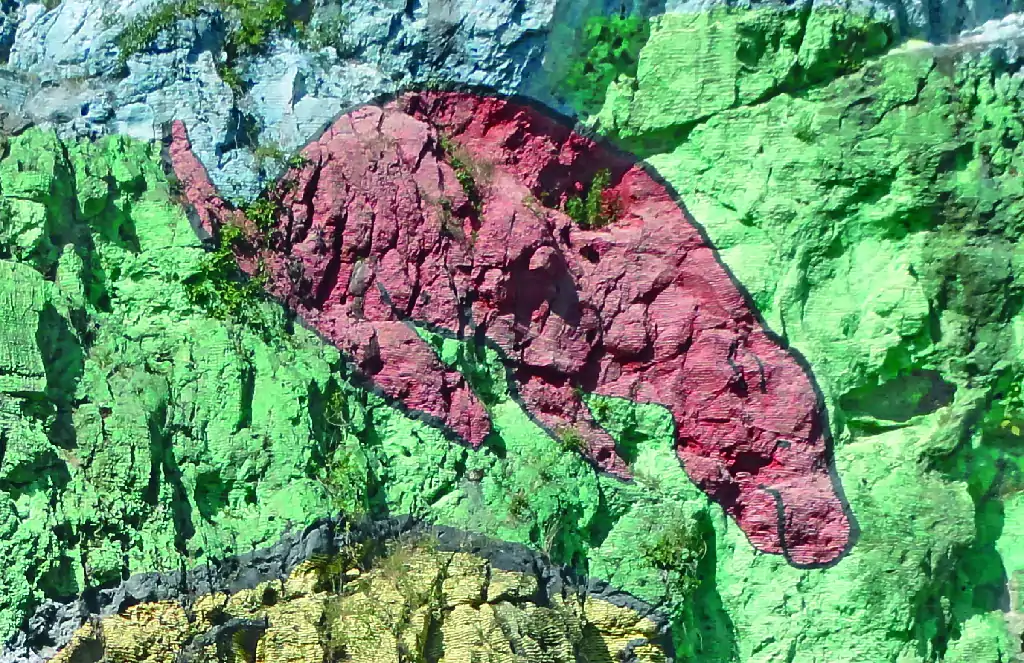

Plesiosaurus, aquatic reptiles from the late Jurassic

In the upper left quadrant, on the blue and yellow background, there are three red figures (two large and one small) representing a family of plesiosaurus, aquatic reptiles with a long neck that lived at the end of the Jurassic (about 150 Ma).

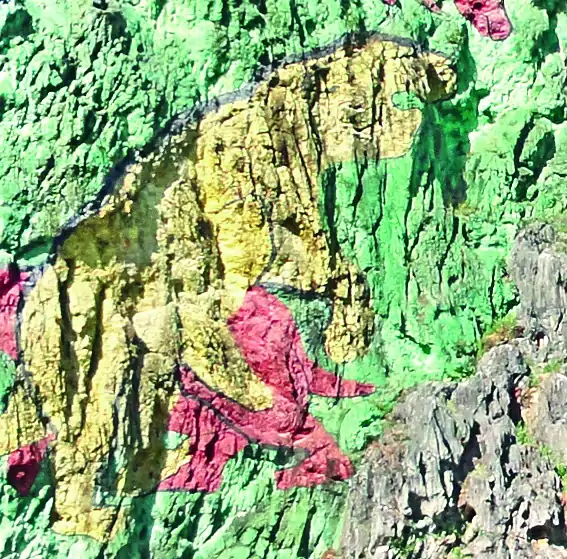

Acratocnus antillensis, an arboreal mammal from a million years ago, and two Megalocnus rodens sloths

In the center, there is an area painted green with three animal figures. The upper one, in red, represents an Acratocnus antillensis,

an arboreal mammal similar to the sloth that inhabited the emerged part of Cuba at the end of the Pleistocene, almost a million years ago. Below, there are two animals, one looking to the left in red and in front of it, another looking to the right in yellow. They are two specimens of Megalocnus rodens, other sloths of large dimensions (they measured 1.7 in length by 1.2 m in height) that lived in Cuba more than 1 Ma and became extinct about six thousand years ago.

Family of aboriginal humans

The right part of the mural is entirely dedicated to aboriginal men. A family formed by a male, a female, and a son, painted in red with anatomical details that the other figures do not have.

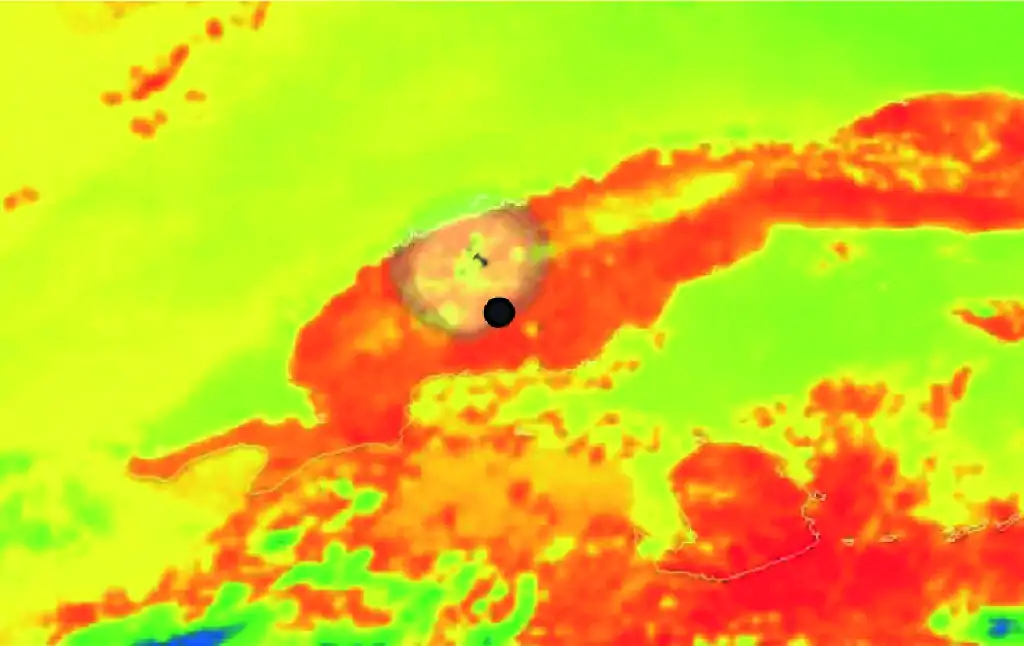

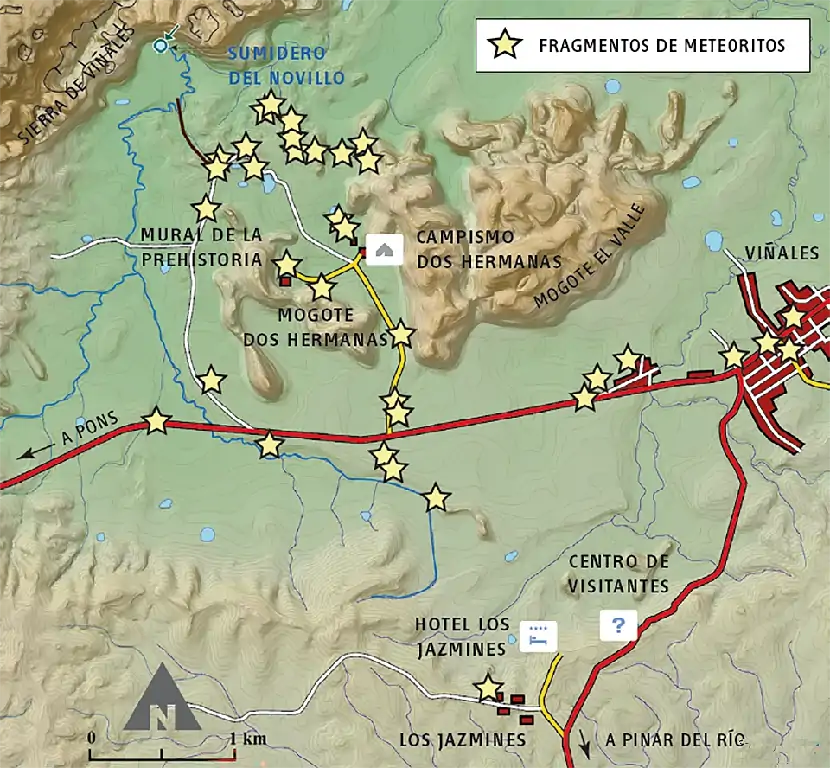

At noon on February 1, 2019, in the province of Pinar del Río, two large explosions were heard, and it was observed that in the sky there was a trace of dark gray to black smoke ending in a lighter gray cloud. At first, it was believed that it could be a plane accident, but later it was certified that the responsible was a meteorite that fragmented into numerous parts that scattered throughout the Viñales Valley, impacting buildings, roads, and the countryside in general. Scientists calculate that the meteorite was traveling at an approximate speed of 70 km/s, which makes one think of a body of considerable dimensions, possibly more than a ton in weight, which generated a great compression of the lower layers of the atmosphere causing the explosion of the body at a height between 80 and 110 km from the earth's surface. From this moment, the meteoroid suffers a deceleration, product of the fragmentation, generating a shower of small meteorites. The specimens collected in Los Jazmines, Viñales, and Palmar have between 3 and 5 cm in diameter, while at the bottom of Dos Hermanas Valley the dimensions of the meteorites are larger, reaching up to 11 cm, with a weight between 0.5 and 1.5 kg. Their composition is of magnesium silicates, in addition to the presence of several metallic minerals, such as iron and nickel. The presence of a fine fusion surface, less than 1 mm, makes one think that we could be in the presence of a stony meteorite, probably of the chondrite type, or stony-metallic, due to the presence of metallic minerals.